Table of Contents

Recursive tilings and space-filling curves

Space-filling curves are continuous surjective functions that map the unit interval [0,1] to a higher-dimensional region, such as the unit (hyper-)cube. They are usually based on a recursive subdivision of the higher-dimensional region into smaller tiles of similar shape, together with a definition of the order in which these tiles should be traversed by the curve.

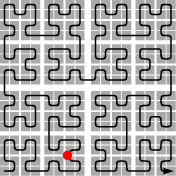

A simple example is Hilbert's curve1). The curve is based on subdividing the unit square into a grid of 2×2 square cells, and simultaneously subdividing the unit interval into four subintervals. Each subinterval is then matched to a cell; thus Hilbert's curve traverses the cells one by one in

a particular order: first the lower left cell, then the upper left cell, then the upper right cell, and finally the lower right cell. The mapping from unit interval to unit square is refined by applying the procedure recursively to each subinterval-cell pair, so that within each cell, the curve makes a similar traversal. The traversals within these cells are rotated and/or reflected in a specific way so that the traversal remains continuous from one cell to another (see figure on the left). The result is a fully specified mapping f from the unit interval to the unit square. For example, f(6/64) would be the point that is reached by the curve when it completes the traversal of the sixth cell in the grid of 8×8=64 cells that results after three levels of subdivision (the red point in the figure).

A simple example is Hilbert's curve1). The curve is based on subdividing the unit square into a grid of 2×2 square cells, and simultaneously subdividing the unit interval into four subintervals. Each subinterval is then matched to a cell; thus Hilbert's curve traverses the cells one by one in

a particular order: first the lower left cell, then the upper left cell, then the upper right cell, and finally the lower right cell. The mapping from unit interval to unit square is refined by applying the procedure recursively to each subinterval-cell pair, so that within each cell, the curve makes a similar traversal. The traversals within these cells are rotated and/or reflected in a specific way so that the traversal remains continuous from one cell to another (see figure on the left). The result is a fully specified mapping f from the unit interval to the unit square. For example, f(6/64) would be the point that is reached by the curve when it completes the traversal of the sixth cell in the grid of 8×8=64 cells that results after three levels of subdivision (the red point in the figure).

A space-filling curve can be used to define an order in which to store or process points, grid cells or other objects in a square or in a higher-dimensional space: we simply process these objects in the order in which we encounter them when we follow the curve. Space-filling curves are used, for example, in databases for multidimensional data, computations on large meshes, and rendering of computer graphics. The beneficial effects of ordering objects along space-filling curves often stem from their locality-preserving properties: consecutive elements in the curve-induced order tend to lie close to each other in space, and vice versa. However, not all space-filling curves are equally effective at optimizing, for example, the disk access patterns of queries in multidimensional databases. In our research, we study different curves and we analyse them using abstract quality measures that are derived from the intended applications. Moreover, we try to find new curves with desirable properties.

My work in this area can be divided into three main categories: (1) exploring combinatorial possibilities for space-filling curves, (2) finding space-filling curves with optimal qualities with respect to certain applications, and (3) representations of space-filling curves, currently, in particular, by sound or by picturing them as trails in three-dimensional mountain landscapes. At the end of this page you will find a fourth category, bycatch: some nice curves and tessellations which I stumbled on accidentally in the course of my research.

Exploring combinatorial possibilities

The following paper describes several space-filling curves and non-continuous space traversals for cubes and simplices in any number of dimensions, and lists a number of open questions in this domain.

- Sixteen space-filling curves and traversals for d-dimensional cubes and simplices.

By Herman Haverkort.

Computing Research Repository (arXiv.org), 1711.04473, 2017.

text; software (contact me)

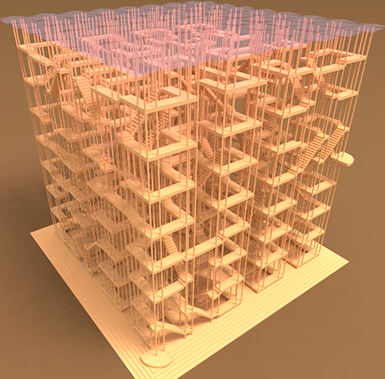

The following paper discusses what possibilities there are for constructing three-dimensional octant-by-octant self-similar cube-filling curves, and what distinct properties the different solutions have. A limited discussion of four-dimensional curves is included as well. The paper comes with a prototype for a software tool to explore the curves.

- How many three-dimensional Hilbert curves are there?

By Herman Haverkort.

Journal of Computational Geometry, 8(1):206-281, 2017.

text; software; list of curves (to test whether the software works correctly on your system).

For entertainment, you may take a look at my labyrinth-style renderings of some three-dimensional Hilbert curves.

Regarding self-similar curves, the following paper has been succeeded by the one mentioned above. However, the following paper also contains some non-self-similar curves that sometimes offer somewhat better locality-preserving properties2) than the self-similar curves:

- An inventory of three-dimensional Hilbert space-filling curves.

By Herman Haverkort.

Computing Research Repository (arXiv.org), 1109.2323, 2011.

text

Face-continuous space-filling curves have the property that the interior of the set of points visited by any contiguous section of the curve is connected. The following paper discusses recursive tilings of acute triangles, and the impossibility of constructing face-continuous space-filling curves based on such tilings:

- Reptilings and space-filling curves for acute triangles.

By Marinus Gottschau, Herman Haverkort, and Kilian Matzke.

Discrete and Computational Geometry, 60(1):170-199, 2018.

edited text from publisher; text from arXiv.org

In three dimensions it seems hard too:

- No acute tetrahedron is an 8-reptile.

By Herman Haverkort.

Discrete Mathematics, 341(4):1131-1135, 2018.

text from publisher; text from arXiv.org

Space-filling curves with optimal qualities

I have studied space-filling curves mostly in the context of optimizing three-dimensional mesh traversals and spatial data structures.

Three-dimensional mesh traversals

Physical processes are often simulated by computations on meshes. A mesh can be understood as a subdivision of physical space into cells of different sizes, depending on the required precision. The simulation proceeds by making several passes over the mesh, each time visiting all cells and updating values stored with its vertices, edges, faces and cells. Space-filling curves, or more generally, recursive traversal orders, can be very useful to organize data transfer, load balancing and mesh refinement in such applications. The following presentation gives an overview of the relevant properties and quality criteria of recursive traversal orders, and presents some results about which combinations of desirable properties can be achieved.

- Space-filling curve properties for 3D mesh traversals.

By Herman Haverkort.

Presentation at Int. Conf. on Parallel Computing ParCo 2013.

slides of extended and updated presentation

Specifically, as explained by Bader, palindromic mesh traversals can be used to organize finite-element and finite-volume computations on meshes such that all storage of intermediate results can be handled by push and pop operations on a small number of stacks. In three dimensions, the Peano curve, based on subdividing cubes into 27 subcubes, is palindromic. I found that there are discontinuous palindromic traversals based on subdividing cubes into only 8 subcubes, and based on bisecting certain shapes of tetrahedra. There are no face-continuous solutions that follow any known recursive subdivision of cubes or tetrahedra into eight similar parts (see the aforementioned presentation; unfortunately I have not found the time to write this down properly yet, but feel free to contact me for further details).

My student Gert van der Plas worked out the discontinuous palindromic tetrahedral traversal in detail. Unfortunately, the rules for which vertices to put on which stacks are quite complicated. I still hope to find some time to write a piece of code demonstrating how it works, also for an adaptive mesh (if there is no unexpected catch). Feel free to contact me to remind me of this plan or to offer your help in trying to simplify the rules.

Spatial data structures

Space-filling curves with good locality-preserving properties

The Arrwwid number of a space-filling curve is the smallest number A, such that any ball with volume B can be covered by A contiguous pieces of the curve of total size O(B). Arguably, sorting points along space-filling curves with low Arrwwid numbers makes for data structures that can be queried efficiently: they would allow any range query with a ball to be answered by scanning only A relatively small sections of the data structure on disk, inducing only A seek operations. In the following paper we study curves with small Arrwwid numbers, and lower bounds on the smallest possible Arrwwid number, in two and more dimensions.

- Recursive tilings and space-filling curves with little fragmentation.

By Herman Haverkort.

Journal of Computational Geometry, 2(1):92–127, 2011.

text slides fast-forward slides

A space-filling curve f preserves locality well, if, for any a and b in [0,1], the points f(a) and f(b) (and maybe also the points f(c) for c∈[a,b]) lie, according to some distance measure, close to each other, relative to b−a. In the following paper we develop a technique to calculate how well a given space-filling curve preserves locality, and we prove some lower bounds on certain locality measures for certain types of space-filling curves.

- Locality and bounding-box quality of two-dimensional space-filling curves.

By Herman Haverkort and Freek van Walderveen.

Computational Geometry, 43(2):131–147, 2010.

text

In my papers on three-dimensional Hilbert curves (see above), we explore locality properties of generalizations of Hilbert's space-filling curve to higher dimensions. The paper mentioned below presents d-dimensional “Hilbert” curves, for any d ≥ 2, with the following property: the size of the minimum axis-aligned bounding box of the points f(c) for c∈[a,b] is never more than 4(b−a). In contrast, with commonly used generalizations of Hilbert curves, the worst possible ratio between bounding box size and (b−a) depends exponentially on the number of dimensions d.

- Hyperorthogonal well-folded Hilbert curves.

By Arie Bos and Herman Haverkort.

Journal of Computational Geometry, 7(2):145–190, 2016.

text

Extradimensional space-filling curves

We can define extradimensional space-filling curves approximately as follows: a D-dimensional space-filling curve F, filling a D-dimensional hypercube U, is extradimensional to a d-dimensional space-filling curve f if, for any d-dimensional face u of U that contains the origin of the coordinate system, the order in which the points of u are visited by F is the same as the order in which these points are visited by f when rotated onto u. For example, some high-dimensional Hilbert curves have the property that the points on most sides of the D-dimensional cube are visited in the order of a (D−1)-dimensional Hilbert curve. In the following paper, we show experimental evidence that four-dimensional space-filling curves that are, to some extent, extradimensional to two-dimensional space-filling curves, can be useful in building data structures (R-trees) that store rectangles in the plane.

- Four-dimensional Hilbert curves for R-trees.

By Herman Haverkort and Freek van Walderveen.

Journal of Experimental Algorithmics, 16, 2011.

text (or contact me for free access)

The following manuscript includes, among other things, families of extradimensional space-filling curves for arbitrarily high dimensions. These could be used, for example, to build R-trees for boxes in three dimensions:

- Sixteen space-filling curves and traversals for d-dimensional cubes and simplices.

By Herman Haverkort.

Computing Research Repository (arXiv.org), 1711.04473, 2017.

text; software (contact me)

More pseudocode and more analysis (proofs) of the extradimensional curves (but with more complicated notation) can be found in the following paper:

- Harmonious Hilbert curves and other extradimensional space-filling curves.

By Herman Haverkort.

Computing Research Repository (arXiv.org), 1211.0175, 2012.

text

Representations of space-filling curves

The order in which plane-filling curves visit points in the plane can be exploited to design efficient algorithms and data structures. Typically, they are useful for their locality-preserving properties: points that are close to each other along the curve tend to be close to each other in the plane, and vice versa. However, sketches of plane-filling curves do not usually show this well: they are hard to read on different levels of detail and it is hard to see how far apart points are along the curve. By drawing the curves as trails in mountain landscapes or building complexes, we can illustrate their locality-preserving properties (and violations thereof) more clearly.

- Plane-filling trails: unbiased visualisations of plane-filling curves

By Herman Haverkort

submitted 2020.

link to explanation, figures, and software

It is hard to draw figures of space-filling curves in three dimensions, and almost impossible to draw figures of space-filling curves in four or more dimensions. I am currently exploring illustrations by means of sound as an alternative. The sound tracks (or the process of creating them) sometimes help to understand the curves better, and at the same time, they seem to provide some insights into characteristics of musical sound.

- The sound of space-filling curves.

By Herman Haverkort.

In Proc. Bridges 2017: Mathematics, Art, Music, Architecture, Education, Culture, pages 399–402, 2017.

text; full report (Aug 2017); and: sound tracks and updates on new approaches

For entertainment, you may also check out my labyrinth-style renderings of some three-dimensional Hilbert curves.

Bycatch

- Nico Bakker's duck plane-filling curve: description and analysis of a curve, found by Bakker, that is defined on a grid of parallelograms and fills a fractal shape in the plane.

- The BMTV triangle plane-filling curve: description of the plane-filling curve filling a fractal “triangle” found by Bandt, Mekhontsev, Tetonov and Ventrella.

- The Rauzy triangle plane-filling curve: description of a plane-filling curve that fills half of the Rauzy fractal.

- Three pretty simple plane-filling curves: three intricate curves, filling beautiful fractallic 3-reptiles, that are obtained by small changes in the definition of the Peano curve.

- Simple plane-filling curves: the root-2 and root-3 families: describes and shows a) the 6 different two equal parts' plane-filling curves, b) the 40 different three equal parts' plane-filling curves that are based on a regular triangle grid, and c) some examples of other three equal parts' fractal curves that might be plane-filing.